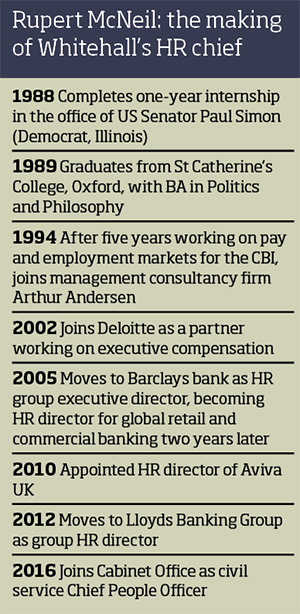

Skills, thrills and Brexit headaches: Matt Ross meets Rupert McNeil

“Victory!” he cries. And Rupert McNeil, the civil service’s Chief People Officer, clenches his fist in celebration.

When I last interviewed McNeil in June 2016, he made clear his hostility to the civil service’s ‘forced distribution’ performance management system – under which managers had to put 10% of their staff into the ‘must improve’ box. Criticising performance management that focuses “too much attention on the process and the mechanics, and not enough on the critically-important human interaction,” he argued against annual reporting and identified a “strong appetite at every level” for reform.

Eighteen months on, that system has been swept away. McNeil is careful not to claim credit for the change: “It was a privilege to watch that decision being taken by the leadership of the civil service,” he says now. “The meeting where it was decided was as good an example as I’ve seen, in any context, of a thorough discussion of a strategically important issue.” But he did play an important role, and got closely involved in the Valuation Office Agency’s pilot of its replacement system.

The VOA’s quarterly moderation meetings were, he says, “very rational, clinical but very compassionate discussions about individuals. I thought: this is what we want.” And under its new approach, he points out, about 8% of staff fall into the “‘must improve’ equivalent.” The requirement to identify 10% as failing, he comments, led to enormous amounts of “energy being expended, when actually you could trust the system to come up with 8%.”

The next decision, he adds, is whether to expand the new system to the Senior Civil Service (SCS): “That discussion hasn’t happened yet, but it doesn’t take a lot to see what my views would be on that.”

These reforms represent a significant change to the way civil servants are managed. But McNeil is also taking a more active role than his predecessors in addressing some of the big policy challenges facing the civil service – and the biggest of all, of course, is Brexit.

As chair of the European Capability and Capacity Board, created to build relevant skills in government, McNeil helped staff up the two Brexit departments and the Cabinet Office team. And reshaping government around the unprecedented challenges of Brexit has, he says, provided “a really fantastic pretext to put into practice some things which we wanted to do as part of the workforce plan”.

In particular, he’s taken the opportunity to improve the civil service’s approach to recruiting and deploying talent across government. The Fast Stream was a crucial source of staff for DEXEU and DIT, he explains, and about 500 jobs went to Fast Stream applicants who’d scored well in testing but not quite made it into the programme.

Effective management of Brexit issues demands collaboration across departmental boundaries. And here, McNeil argues that the civil service is starting from a good place: “The culture is actually very naturally collaborative – although it may not always appear like that to people when they’re in it!” he says, smiling. It’s also, he says, good at learning rapidly how to deal with new challenges. But he does identify one important weak spot: “Sometimes the problem isn’t one of intellect or of challenge; it’s about whether the right technical skills are in the room.”

McNeil – himself a technical specialist, recruited from outside government after a career in HR – believes that “the job of the professional – the HR, the commercial, the policy professional – is to protect amateurs from the counter-intuitive.” In other words, solutions that sound like common sense to the generalist can produce bad outcomes when applied in the complex worlds of specialist and technical delivery.

“If you look at the West Coast Mainline, the right technical skills weren’t there; you could argue that’s also true of what Chilcot found,” he argues. “We need to teach people to know what they don’t know, so they can bring in the right skills.”

Indeed, skills seem to dominate McNeil’s in-tray. He proudly reports that all online Civil Service Learning courses are to be provided without charge, removing “a source of friction that was deterring people”. And he says officials will soon have access to a “line management fundamentals package, accompanied by a self-assessment tool”.

Meanwhile, the civil service professions are becoming more involved in training; this, he says, is a “really fantastic thing that’s happened over the last 12 months”. And as well as developing their own specialist skills, McNeil adds, civil servants “need to be able to manage people with different technical backgrounds from theirs – whether it’s me coming in and having to work with policy people or parliamentary counsel for the first time, or vice versa.”

So one of the new Civil Service Leadership Academy’s three learning strands, he explains, will examine “how you lead in a multi-disciplinary context”. The academy has already run training in parliamentary procedures, and other professions such as commercial and digital are developing courses: “It’s the job of a profession to say what it thinks other people need to know about that profession,” he adds.

A second strand, Basecamp, helps new SCS staff to become “good organisational leaders”. The programme runs for a year, and is being rolled out for directors and director-generals. And the third strand involves dissecting case studies of civil service delivery.

Here, explains McNeil, programme leaders haven’t been afraid to examine the civil service’s failures as well as its successes – with West Coast Mainline and Chilcot on the agenda as well as the Scottish fiscal framework and the response to Ebola. The first two, he says, “go in the ‘blunders of our government’ category,” with the Iraq course “building on work that’s been done with the Ministry of Defence on lessons from Chilcot, particularly on challenge.”

That seems particularly appropriate now, I suggest – for Brexit has both sharpened the need for civil servants to speak truth to power, and fostered public attacks on officials suspected of questioning the Brexit project. Will the Academy give civil servants the skills and confidence to offer appropriate challenge? “I think, in a sense that’s the most important thing that gets delivered through this,” he replies. “And I think it’s also what makes very senior people – permanent secretaries – want to be involved and to share their thinking.”

As the civil service develops its specialist professional skills, it will have to pay just as much attention to retaining them – for, as McNeil’s own career demonstrates, many of these skills are valued in both the public and private sectors. Yet many civil service packages are no longer competitive, and the Budget crushed hopes that the Whitehall pay cap might be relaxed.

Quite a lot can be achieved without lifting the pay cap, McNeil believes. “We’ve got tools that we didn’t have before, particularly with the professions,” he notes, pointing to the digital functions’ establishment of a cross-government system of job families and capability levels. Below SCS levels, this enables departments to improve pay parity across the civil service by adjusting allowances. In this case, he adds, the changes are being funded by replacing expensive contractors (see Truth to Power, p30) with permanent staff.

“The current SCS arrangements encourage people to move too rapidly.”

“That type of intelligent thinking about interdepartmental comparisons and how you structure pay needs to happen across all the professions,” says McNeil. “And it becomes particularly important with hubs, where you’ve got people from different departments sitting alongside each other doing similar jobs.”

This approach is harder with SCS jobs, he accepts – but here, the challenges are also different. “The problem is that the current arrangements encourage people to move too rapidly,” he argues. “We want to look at ways in which people can be recognised in pay terms for staying in one role and acquiring more skills.” This goal will feed into his response to the Senior Salaries Review Board, which has “been very good and challenging of us, saying: ‘What does the SCS of the future look like? What are you trying to hit in terms of your approach to pay?’”

These sensitive pay issues are, McNeil acknowledges, much more easily addressed within a functioning industrial relations framework – and he agrees the current arrangements aren’t up to scratch. His new Executive Director for Employee Relations, Mervyn Thomas, has been tasked with “building the architecture for really effective industrial relations, because somewhere along the line we’ve lost that a bit – and with it, lost a really effective set of channels.”

The civil service collaborated effectively with the unions on pensions, he argues, recruiting them onto a Pension Scheme Advisory Board. “That’s working really well as a technical advisory group,” he says. “Imagine that happening on estates and locations; training; diversity and equality; pay and productivity. These are all conversations we should be having with union partners.”

It certainly helped in refashioning performance management, he adds: “We had really, really good conversations with the unions, and that’s made the product much better.”

Besides performance management, there’s one other topic that McNeil plainly feels truly passionate about: diversity. “There are lots of things I want to do whilst I’m privileged to be doing this role, but I will be very disappointed if we haven’t moved on two things by 2020,” he says. “One is to make a real dent in the representation of [minority] groups. And the other is being able to say that we are the UK’s most inclusive employer. I feel that accountability very strongly.”

The Civil Service Diversity and Inclusion Strategy, published in October, promises targets for the representation of ethnic minority and disabled staff within the SCS by 2020. Departmental goals, McNeil explains, will be published by next April and incorporated into permanent secretaries’ performance objectives.

To create the system change required for departments to hit those targets, a task force has been established – chaired by civil service Chief Executive John Manzoni, and supported by a dedicated team. “We’ve seen real traction on disability and workplace adjustment by taking that approach, and we’re going to be looking forensically at how we can support individuals into the SCS,” he says. “We want to demonstrate to the best ethnic minority talent in the UK that the civil service is the place to work.”

On this topic, McNeil’s passion is clear. And now that performance management has been reformed, he’s bringing the big guns to bear on the civil service’s rejuvenated diversity agenda. For a shift this complex and wide-ranging, ambitious diversity targets would present a tight deadline. But whatever goals are set, I, for one, wouldn’t bet against him crying “Victory!” on diversity in 2020.

Related News

-

FDA celebrates Women’s History Month 2025 with panel event

To celebrate Women’s History Month and International Women’s Day 2025 the FDA hosted a panel event looking at the history of women in the civil service and within the trade union movement.

-

FDA attends TUC Women’s Conference 2025

A delegation of FDA members attended TUC Women’s Conference 2025, held in Congress House, London, from 5-7 March.

-

FDA panel event for LGBT History Month 2025

To mark LGBT History Month 2025, the FDA hosted an online panel event with members and representatives from civil service-wide networks to discuss the progress and challenges of advancing LGBT equality and inclusion in their workplaces.