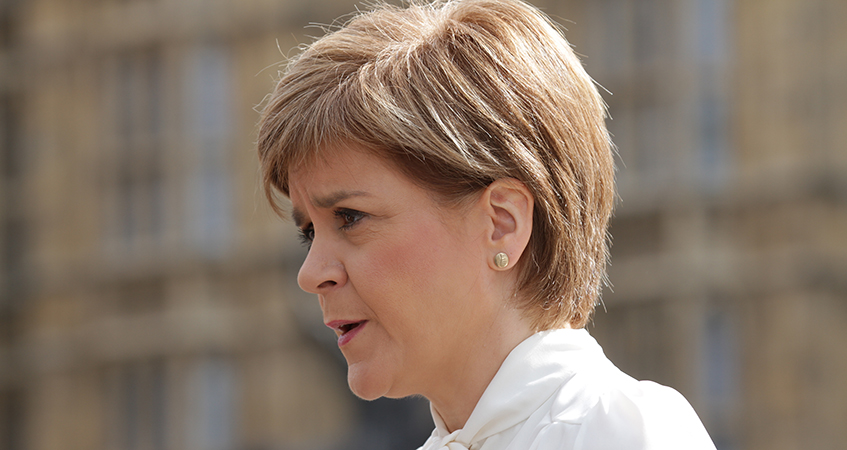

Nicola Sturgeon: Why an impartial civil service is a strength for MSPs

The following words are First Minister of Scotland Nicola Sturgeon’s contribution to this work.

This year, the Scottish Parliament celebrates its 20th birthday. When the parliament first reconvened in 1999, the Queen presented it with a newly-commissioned silver mace.

The mace was inscribed with the words “wisdom”, “justice”, “integrity” and “compassion”. Those words are intended to serve as a reminder and an inspiration to elected representatives of the enduring values that the new institution was expected to exemplify. The words on the mace also summarise qualities that characterise the civil service at its best. However, for civil servants, a fifth watchword, “impartiality”, is also central to their duties.

Throughout the 20 years of devolution I have had the privilege of serving as an MSP, and for the last 12 I have had the honour of serving in government – initially as Deputy First Minister, and now of course as First Minister. My experience throughout that time has reinforced my view that the impartiality of the civil service is an important asset. It should be preserved, protected and valued.

My experience throughout that time has reinforced my view that the impartiality of the civil service is an important asset. It should be preserved, protected and valued.

Impartiality is not the same as neutrality. The civil service supports the government of the day – it actively helps us to deliver our policies and priorities. However, the current SNP administration knows – as all political parties at Holyrood know – that any elected government, regardless of party, would receive exactly the same level of commitment and support.

The crucial benefit of this approach is that it allows governments to inherit, and benefit from, experience and expertise which officials have earned during previous administrations. I saw this at first hand in 2007, when the SNP formed its first government. At that time, devolution was eight years old. Both previous administrations in Scotland had been coalitions between Labour and the Liberal Democrats. The civil service had no experience, in a devolved context, of serving any other parties.

It was immediately obvious, however, that the civil service was as committed to supporting the aims and policies of an SNP minority administration, as it had been to supporting the previous coalition.

In the first few months of our administration – alongside a whole range of other work, such as abolishing bridge tolls and establishing an independent Council of Economic Advisers – ministers and civil servants jointly developed a new national purpose to unite the work of all public sector organisations in Scotland. This was supported by a national performance framework, underpinned by outcomes.

Since those initial months, that joint work has continued. The civil service has been essential to the delivery of every significant achievement of the Scottish government – including passage of the Climate Change Act in 2009, the successful implementation of minimum unit pricing for alcohol, the restoration of free university tuition and the delivery of major infrastructure projects such as the Queensferry Crossing.

Current SNP administration knows – as all political parties at Holyrood know – that any elected government, regardless of party, would receive exactly the same level of commitment and support.

An obvious – and very difficult – test for the civil service was the independence referendum of 2014. In my view, the civil service in Scotland did a testing job very well. It provided full support in developing policies and providing advice for the creation of an independent Scotland. However when, in the run-up to the 2016 Scottish parliamentary election, it held discussions with other parties about their plans for government, it was obvious to them that – as always – the civil service would provide full support for whichever government was elected.

Almost inevitably, I’ve placed an emphasis here on high profile projects and events – however that does not cover the other significant work of the civil service. For many important areas, the success of the civil service can be assessed by the fact that they are not being widely noticed! Simply by helping ministers to respond to correspondence and questions, civil servants improve the transparency and accountability of government.

For many important areas, the success of the civil service can be assessed by the fact that they are not being widely noticed! Simply by helping ministers to respond to correspondence and questions, civil servants improve the transparency and accountability of government.

None of this means that our relationship with the civil service is always tension-free. I still occasionally get frustrated at the quality of briefing I receive. Officials could perhaps sometimes do better at placing themselves in ministers’ shoes, and considering what information we really need for particular meetings or engagement – it won’t always be a series of lines to take. However, I am sure that ministers are sometimes a source of frustration for civil servants too!

But on the whole, my experiences of working with the civil service have been overwhelmingly positive. It is maybe also worth noting that – despite the inevitable tensions that sometimes arise – the civil service in Scotland has often worked well with the wider UK civil service. I still see the Edinburgh Agreement between the UK and Scottish governments – which paved the way for the 2014 referendum on independence – as being a model of its kind. It reflected well on the professionalism of the UK civil service as a whole.

Our experiences here have been mixed, however. The Scottish government has also had to work with the UK government on the aftermath of the 2016 referendum on leaving the EU. The UK government has routinely deprived Scottish government civil servants of important information (for example on preparations for a “no-deal Brexit”) which I would expect to be made available. This is perhaps a reminder that – regardless of the professionalism and goodwill of civil servants – clear leadership from ministers is still absolutely essential if government is to function effectively.

Looking ahead, the coming years will see the implementation of new powers for the Scottish Parliament, and I hope another opportunity for the people of Scotland to consider independence. All of this will mean new tests for the civil service. The development of the Scottish Social Security Agency is a good example of an entirely new challenge.

Regardless of the professionalism and goodwill of civil servants – clear leadership from ministers is still absolutely essential if government is to function effectively.

It requires a strong focus both on project management and on values. In fact, the values underpinning the new agency – a respect for human rights and human dignity – are essential to its project management. They provide the sense of shared purpose that can unite people who are delivering a complex operational project.

That is why, when we revised the national performance framework last year, we included a statement of values. They made it clear that government and public services must treat all people with kindness, dignity and compassion. We believe that those values should underpin our public services, and indeed we hope they will characterise Scottish society as a whole.

The new national performance framework – like the parliament’s mace – reflect the fact that enduring values are crucial, even as we establish new institutions and meet new challenges. For the civil service – which has been so central to the success of devolution so far – those values will continue to include impartiality.

It is a source of strength, for MSPs of all parties, that the civil service exists to serve the public as a whole, rather than being affiliated to a specific party. For that reason, there is a broad consensus in Scotland about the benefits of an impartial civil service. I hope, and believe, that that consensus will continue for many years to come.

Related News

-

Government has “no strategy” on long-term pay and reward issues, says Penman

FDA and IfG hosted a joint fringe event at this year’s Labour Party Conference in Liverpool, discussing ‘Should public sector pay and pensions be reformed?’

-

FDA at Fast Stream Base Camp 2025

FDA Fast Stream reps have been in Birmingham for Fast Stream Basecamp, welcoming new first year Fast Streamers, speaking to them about the union’s work and how to get involved.

-

“Significant gaps” in current Northern Ireland standards regime, says Murtagh

FDA National Officer for Northern Ireland Robert Murtagh has called for a strengthened standards regime in Northern Ireland government.