Carillion: After the fall

The hastily-scrawled graffiti on the building site fence said it all: ‘Carillion. Bust’. At the start of this year, 43,000 employees awoke to the devastating news that the construction giant had gone into liquidation, putting at risk their livelihoods and raising major questions about how and why their employer had been allowed to fail so spectacularly. Workers on the company’s construction sites reported being sent home that same day and, as PSM went to press, more than 1,400 former Carillion employees had been laid off.

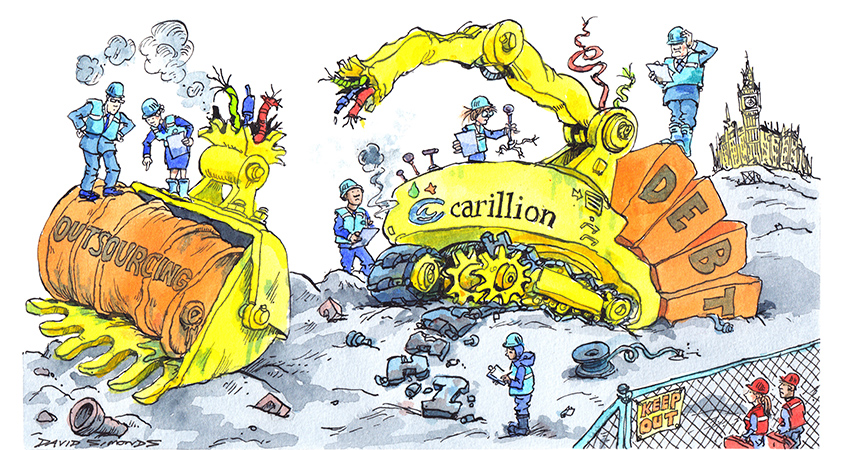

Already the blame game has started, and those arguing for an overhaul of Britain’s corporate governance laws have a new case study to point to. When it collapsed, Carillion had one of the largest pension deficits of any FTSE 350 company, and was mired in debt – owing around £2bn to its suppliers alone.

But beyond the personally traumatic tales of lost jobs, unpaid bills and pensions at risk, Carillion’s collapse has strengthened the hand of long-standing critics of public sector outsourcing, and led to renewed questions about how the government manages its contractual relationship with private firms.

The firm was one of the biggest suppliers to the UK public sector, responsible for 450 government contracts covering everything from maintaining accommodation for members of the armed services to constructing key parts of the High Speed 2 rail link. Carillion provided catering for schools, looked after hospital buildings for more than a dozen NHS trusts, and managed prisons for the Ministry of Justice. It was deemed so important that it was named as one of the government’s “Strategic Suppliers”, with a designated Cabinet Office official tasked with monitoring the firm’s performance.

Warning signs

MPs demanded to know why key warning signs – increasingly late payments to suppliers, a major profit warning in July 2017 – were missed by government, which continued to award contracts to Carillion almost to the end. Ministers have fast-tracked the Official Receiver’s own probe into the causes of Carillion’s failure. And opposition leader Jeremy Corbyn has called for an end to what he called the public sector “outsourcing racket”. So what is the state of play in the UK outsourcing market – and where should officials turn their gaze as they try to learn from Carillion’s demise?

“Their core skill has become bidding for contracts with government, not doing whatever it is they were supposed to be doing”

– Prof Colin Talbot

Professor Colin Talbot of Cambridge University has long studied civil service procurement practices and has advised organisations bidding for public sector contracts. He tells PSM that, while officials may have feared the worst for Carillion, the sheer size of such firms means public intervention can be highly risky. Firms like Carillion are “publicly listed companies who are heavily reliant on borrowing to keep them going,” he says. “If you do anything that makes it clear they’re in trouble, you’re likely to trigger exactly the sort of problem you’re trying to avoid”.

albot does believe that ministers’ tendency to see outsourcing as the solution to a whole series of public policy challenges – often for purely ideological reasons – has resulted in a marketplace dominated by big players who have moved far beyond their original areas of expertise. “Their core skill has become bidding for contracts with government, not doing whatever it is they were supposed to be doing,” he says. “You end up with Carillion – basically a building company – doing things like serving school meals.”

Nick Davies keeps a close eye on the government’s handling of commercial contracts as associate director of the Institute for Government think tank. He warns that the bidding process, which can run to “thousands of pages”, deters smaller firms for bidding for contracts. “Clearly that favours organisations that have expert teams that are used to bidding day in, day out and for whom that’s the only thing that they do,” he tells PSM.

That’s a view echoed by Kerry Hallard, chief executive of the Global Sourcing Association, which represents specialist suppliers in areas such as IT and digital. She warns that the sheer time and energy involved in bidding for public sector contracts means the industry is “entering into a fairly monopolistic position with the really big players”. She points the finger at EU public procurement rules, which she says place heavy burdens on smaller suppliers. While her industry was overwhelmingly opposed to Brexit, she suggests the prospect of a procurement shake-up after the UK’s departure may be a “silver lining” for smaller players in the industry.

Austerity procurement

Hallard also argues that years of “austerity procurement”, with an excessive focus on driving down costs rather than long-term thinking about the quality of services, means that Whitehall is all too often “shopping as opposed to entering into a collaborative arrangement that focuses on the end goal”. She calls for a more “grown up” conversation between public and private sector, and says civil servants and ministers “need to accept that the service provider needs to – and must – make a profit from the work that they do. If not, why would they be in it?”

But are civil servants not right to be cautious following the string of high-profile outsourcing failures in recent years – such as the bungled security arrangements at the 2012 Olympics and last year’s early termination of the East Coast mainline rail franchise, to name but two? Hallard accepts that some parts of the industry need to change their behaviour, but says the public sector needs to ditch “an ingrained mentality” which refuses “to accept the way that the private sector works”.

“These are the people negotiating massive, multi-billion pound contracts. It’s like fielding Ronaldo against a player from Stroud.”

– Kerry Hallard, Global Sourcing Association

“I think there is over-compliance and a massive fear factor all the time about getting things wrong. That happens in the private sector as well as in the public sector. But more than anything, I think there is just a tribal sort of mentality of ‘I’m the customer, therefore I’m always right. You’re the service provider and you’ve just got to do it’. That’s not what a collaborative, forward-thinking partnership should look like.”

Skilling up in Whitehall

Skilling up in Whitehall

Senior officials have robustly defended the Cabinet Office’s relationship with Carillion, claiming that the civil service has never been as well-placed as it is now to weather such a storm.

Civil service chief executive John Manzoni has pointed out that many of Carillion’s contracts were run as joint ventures at government insistence, meaning that fellow suppliers could step in to ensure continuity of service. Ministers also moved quickly to put Carillion into the hands of the Official Receiver, with an instruction to keep vital services running – a “quite a deliberate act”, Manzoni says, which followed extensive contingency planning.

Manzoni insists officials went to great lengths to limit the risk to taxpayers. “This is certainly not an example of too big to fail,” he told MPs earlier this year. “This company has failed and its shareholders and lenders have been wiped out to the tune of billions of pounds. That’s genuine failure… What we’re doing is paying for services that the public sector is going to receive.”

Cabinet Secretary Sir Jeremy Heywood meanwhile denied claims that the civil service had failed to learn the lessons of previous contracting failures – in particular the 2013 scandal which saw firms overcharge the Ministry of Justice for the electronic tagging of offenders. He said the government had “absolutely prioritised” building its commercial capability in recent years, “bringing in more people from outside” and “having much more of a grip at the centre”.

“This is certainly not an example of too big to fail”

– Civil Service CEO John Manzoni

The Cabinet Secretary added: “No doubt [the collapse of Carillion] is a bad outcome for the country, but the work that we have done in the commercial profession, trying to understand across 450 public sector contracts what will happen in this worst-case scenario, is work that ten years ago the commercial function in the civil service would not have been capable of doing. It would not have known where to start, frankly.”

But other observers say there is still scope for Whitehall to sharpen its commercial acumen, and they raise questions about whether the civil service is attracting the people it needs to hold its own in negotiating with suppliers.

Cambridge University’s Colin Talbot says commercial skills in government remain too generic, focusing on training people to design repetitive bidding processes rather than encouraging them to become real experts in the services they are buying. “One week they could be doing something on purchasing a new motorway, and the next purchasing catering facilities for the prison service or something,” he explains. Talbot also believes that the recent trend of centralising commercial expertise in the Government Commercial Organisation is a backward step, aimed at cutting costs rather than improving procurement.

“Under the last Conservative government, before New Labour came in, they spent ages decentralising functions, including commercial management,” he says. “The argument there was ‘stick to the knitting’ – that the way to get high performing public sector organisations was to have ones which were very specialist and functional in a particular area, ones which developed a high degree of skill and knowledge about their own business. And therefore they were the best people to be buying stuff, rather than having a one-size-fits all, generic purchasing facility across government.”

The Institute for Government’s Nick Davies acknowledges that central government has become “a much more intelligent client than it once was”, but he too believes that individual departments must give more seats at the top table to commercial experts. “Most people at the top of departments tend to be policy professionals rather than commercial professionals, and there’s a question of when in the policy and decision-making process those commercial experts are being consulted,” he says.

For her part, Kerry Hallard argues that Whitehall’s commercial function will continue to face an uphill struggle because of the “disparity of pay” between the public and private sector. “These are the people negotiating massive, multi-billion pound contracts,” she says. “It’s like fielding Ronaldo against a player from Stroud. Can you have the same matching skillset when the private sector is paying somebody £500,000 and the public sector has somebody on £90,000 or £100,000 a year?”

Talbot agrees: “You need people who intimately understand the business that they’re buying for – and you need to pay people to do that. Purchasing managers in the private sector are quite well remunerated. That’s why quite a lot of public servants go over to the private sector when they get those skills.”

Unpicking the causes and policy implications of Carillion’s collapse will be no easy task, but it has given the opponents of outsourcing a powerful argument for radical change. The onus is now on ministers to explain how outsourcing can work better for the public – and how they will invest in the people they ask to fight for taxpayers’ interests whenever the government signs on the dotted line.

Related News

-

FDA rejects claims civil service to blame for delays to Northern Ireland infrastructure projects

The FDA’s National Officer for Northern Ireland Robert Murtagh has spoken out against claims that the Northern Ireland Civil Service, were to blame for the failure of infrastructure projects to be completed on time.

-

Penman joins panel discussion on ethical leadership in government at IfG ‘Nolan Principles at 30’ conference

FDA General Secretary Dave Penman took part in a panel discussion covering the question ‘How can politicians demonstrate ethical leadership?’.

-

Carers Week 2025 – launching our Carers’ Survey

To mark Carers Week 2025 (9-15 June), the FDA is launching a survey of carers in the civil service to find out what progress has been made since our 2021 report, and what still needs to be done.