BAME representation at the top: how do we get there?

“Organisations,” as former MiP Chair Zoeta Manning told us, “should represent the population they serve.” The leadership of our public sector should represent the British public.

Progress has been made, but there are still blocks preventing BAME individuals from accessing roles in the senior civil service and top management of the NHS. This Black History Month, we looked to both the past and the future to find out how to tackle these blocks. We spoke to our activist members about what they’ve done to tackle recruitment discrimination – and what needs to be done to help achieve true representation at the top.

Tolu Oyelola

Tolu Oyelola originally came to the UK to study for a postgraduate degree in law: the plan was to finish his studies and return to Nigeria, where he would become a lecturer. But he needed money to fund both his studies and living expenses, so he applied for a job at the Inland Revenue. 29 years later, he’s “still here”, a member of HMRC’s SCS.

When Oyelola first joined Inland Revenue, it seemed to him that you “waited your turn” for progression. Then the process changed to a competency-based system – one where you had to sell yourself to get a better role.

“I shouldn’t over-generalise, but certainly in my part of Africa and my family it was considered bad taste to boast about your achievements,” Oyelola tells us. Modesty was a key value. He accordingly saw this new system as “ridiculous” and thought it wouldn’t last long, so “the best thing to do was to sit it out. In time the designers of this process would come to their senses.” It took “quite a few years”, he admits, for him to realise this wasn’t going to happen. Oyelola believes this difference in cultural norms continues to be a problem for some civil servants. If you are competing with people brought up to sell their achievements, “it’s not even a competition at all.” Oyelola believes we need to provide support to people with his kind of experience, to make sure they are comfortable putting themselves forward for promotion.

Oyelola joined the FDA at the same time he joined the civil service, but only engaged with Black History Month for the first time a few years ago, where he was the panel for an event. From this, he was asked by the union to chair its London BAME into Leadership conference.

Run by the FDA and Dods, the BAME into Leadership events focus on helping civil servants from ethnic minority backgrounds build networks, overcome barriers and realise their leadership aspirations. Oyelola has now chaired two of these conferences and was part of the committee looking into the event programme for the 2019 event. “On the day,” he tells us, being a Chair is about “being inspiring and making sure that [things] run to order.”

How does he inspire? “I try to lead by example,” Oyelola says. “Although I am not particularly keen to talk very much about myself, I did start this year’s event by talking about my role in HMRC and how the fact that I’m playing a very small role in funding our public service inspires me, and gets me out of bed in the morning.” Oyelola cites Nelson Mandela and Barack Obama as leaders who have inspired him. They were “people who, on the face of things, were fairly measured in their words, chose their words carefully, and weren’t prone to extreme reactions to things.”

Asked why he believes these events are important, Tolu says it’s the “networking” effect, “the opportunity to see so many senior leaders – BAME leaders – in one place at a time,” which is “something that is very unusual.” For these people to then speak about their experiences, and how they got to where they are, “is very inspiring to junior colleagues.”

Visibility, Oyelola argues, is also important when it comes to tackling discrimination. By being in a leadership position, he feels able to discredit the stereotypes which are still “alive and well” within the civil service.

Oyelola tells us “there are things that need to be done in terms of positive action that the civil service is still reluctant to do.” He points to the example of the Rooney Rule in the states, a National Football League policy that requires ethnic minority candidates be interviewed for coaching positions. African-American coaches, it was found, were less likely to be hired and more likely to be fired than their white counter-parts, and this rule sought to address this imbalance. “The idea wasn’t to give them preference in any way, they would still have to go through the same process,” Oyelola elaborates. Ahead of the Rooney Rule, only 6% of coaches were black. By 2006 – three years after it was instated – this percentage grew to 22%.

“I think the civil service really has to start thinking of doing things like that,” Oyelola says. Though he is “very, very, very uncomfortable about positive discrimination” (“things are hard enough as it is, I wouldn’t want anyone thinking I got my job just because of the colour of my skin”), the senior civil servant believes “we need to start thinking outside the box.”

Zoeta Manning

Zoeta Manning’s mother wanted her daughter to be a nurse. Why? “Because I was always looking after everybody, that’s just my nature.” Not wanting to pursue a clinical role (Manning was not a fan of blood), she still wanted to support her community, and joined the NHS in a non-clinical capacity. Starting as a medical secretary in a GP’s office, Manning rose through the ranks, and is now a Senior Integration Manager for frailty. She went to night school to obtain her Bachelor’s, and is now studying for a MSc in Healthcare Leadership. “That’s why I really support my admin staff to develop,” she explains, “because I’ve been there. And I can see their capabilities, when perhaps other people don’t see their capabilities.”

Manning’s belief in helping people makes her a natural trade unionist. In one of her previous roles, she had an incident with a manager which led to taking out a grievance. She received the backing of her union, and was helped by MiP National Officer Pete Lowe. “It was so good to have somebody to support me,” she says, as she was feeling “quite vulnerable.” Lowe then went on to suggest Manning get more involved in the union herself. Though initially hesitant, Manning thought that she would like to support someone who went through what she had “and have the choice to have somebody who looks like me represent me.” Soon, she was representing the West Midlands on MiP’s National Committee, then became the organisation’s Vice Chair, before being elected its chair in 2013.

“I’m passionate about representative leadership,” Manning tells us. “Unless people can see that we can get to these levels, they’ll think they can’t because they’ve never seen anybody at this level.” Manning has also represented the FDA and MiP five times at the TUC’s Black Workers’ Conference, and spoke three times on motions advocating for increased racial diversity at senior levels of organisations.

When asked about unconscious bias within public sector organisations, Manning says that she believes the phrase is “quite politically correct – I would say there’s conscious bias. We’re not where we are by accident, some people want to keep the status quo – keep things as they are. Better at disguising their prejudice than they have been in the past, more subtle now, but it’s still there.”

“When governments realised the situation with women not being on boards, they gave them targets. We’re still not there yet, but it did make them pull their finger out, didn’t it? But when you mention it about BAME people, everybody throws their hands up in the air and says ‘oh, we can’t give them targets!’ I don’t see what the difference is. If you can see a gap, and you can see that you need some positive action – that’s all it is, not a new concept – why can they do that for one group and not another?”

Hakim Din

When asked which leaders inspire him, Din – like Oyelola – names Nelson Mandela, but also Che Guevara. “Because of his principles,” he elaborates. “He never budged from his principles.” It is easy to see how Din has been influenced by these two men, as he has spent his career standing by his principles and fighting discrimination, in schools and the civil service.

Din wanted to make a difference, and education “was the obvious place to go.” He especially wanted to help BAME kids, and argued if people like him “don’t get into the system and try and change it, nobody will.”

Schools were not the only place where Din fought discrimination. He was part of a group that established a Black Members’ Committee within the Scottish Trade Union Congress (STUC), which led to Black Members’ Conferences. When he became a member of the FDA, he continued to work with his new trade union to promote race equality.

Din and FDA colleagues joined up with activists in Prospect and PCS to create a Race Equality Network, which received the full support of the Scottish Government Permanent Secretary. In fact, he opened the first meeting, and informed all other departments of the Scottish Government of what he had heard during it, and encouraged them to get involved. Having this buy-in, Din explains, “closes the loop” – it is one thing to make equality policy, but quite another to know the most powerful civil servant in the government is actually supporting it.

Now representing the FDA, Din continued to raise motions at the STUC and work with other anti-racist organisations, including Show Racism the Red Card. In addition to this, he was a member of the group that founded our BAME into Leadership conferences. People have told him they’ve become SCS as a result of “coming to these conferences, networking, hearing what people are saying” and securing mentoring through these events. “One of the women who came to this event is now a Deputy in her department in the House of Commons,” he tells us.

Though proud of his achievements, Din knows there is more that needs to be done to achieve true racial equality within the civil service. “We’ve got processes, we’ve got policies,” he says, “but who’s actually monitoring the policies, monitoring the changes that are needed to take place?” Change has to be constantly embedded throughout recruitment practices, to make sure there is a consistent approach to tackling discrimination.

While believing it’s good to have a BAME person on an interview panel, for example, who can “look at the cultural nuances in answers, and intonations”, Din doesn’t believe the onus to fight racism should be on a single person. It is more important, he argues, to ensure “everyone on the panel is more aware”, as these are issues that everyone needs to know about. “White people need to be part of the change, he says, “and there are a few who truly are!”

Related News

-

Carers Week 2025 – launching our Carers’ Survey

To mark Carers Week 2025 (9-15 June), the FDA is launching a survey of carers in the civil service to find out what progress has been made since our 2021 report, and what still needs to be done.

-

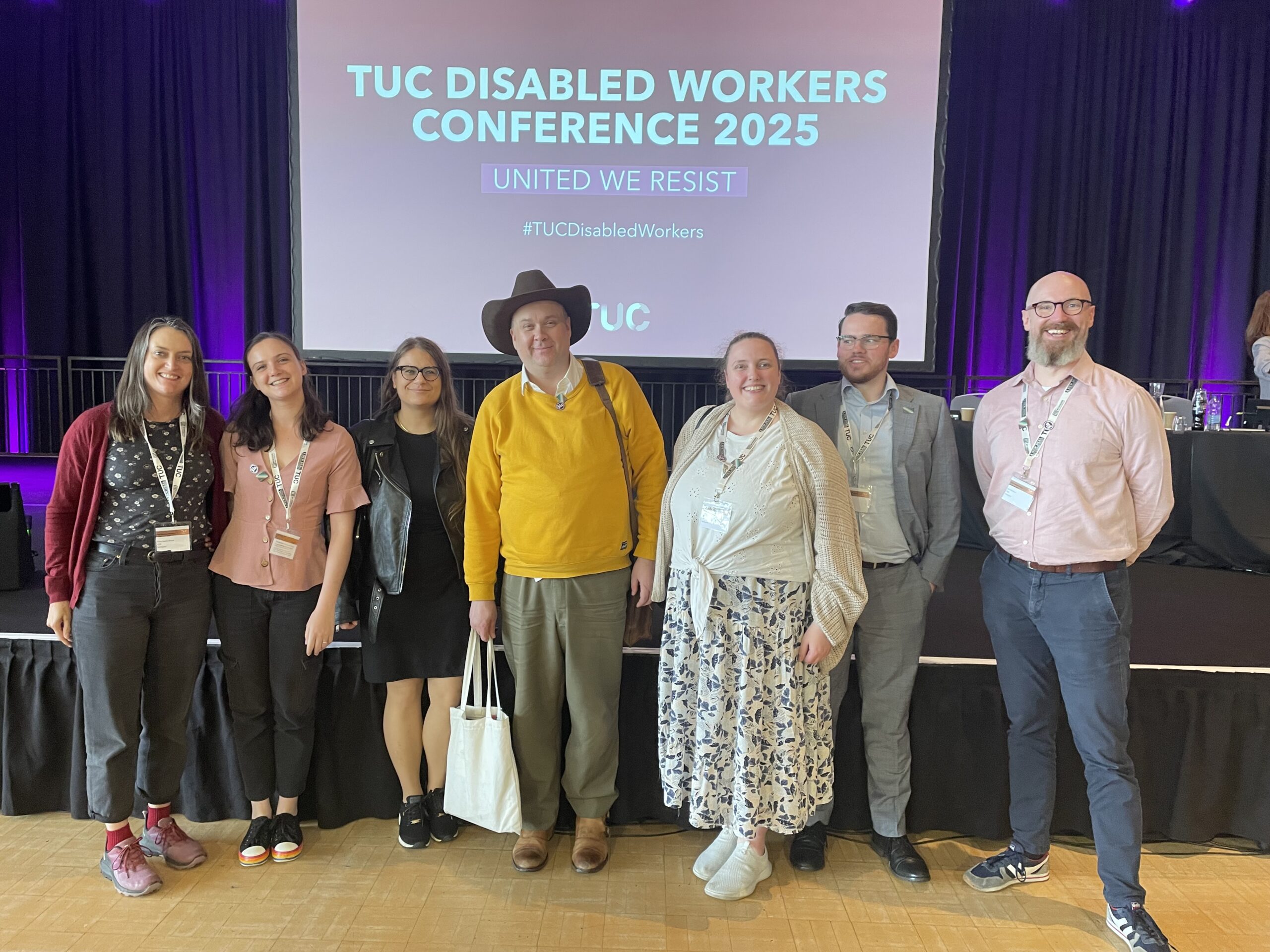

FDA delegation attends TUC Disabled Workers’ Conference 2025

Last week, an FDA delegation attended the TUC’s 2025 Disabled Workers’ Conference, held at the Bournemouth International Centre. The conference brings together delegates from across the union movement to discuss, debate and decide motions on issues affecting disabled workers.

-

FDA rejects Reform’s “nonsensical” claims on EDI spending

The FDA has rejected claims made by Reform UK that £7 billion could be saved by cutting Equality Diversity and Inclusion initiatives, despite the most recent Cabinet Office review showing civil service EDI spending was around £27 million.