Jill Rutter: Will civil service impartiality be a casualty of Brexit?

This year, the Smith Institute released an FDA-commissioned report entitled ‘Impartiality matters: The importance of impartiality in a “post truth” world’.

Comprised of essays written by former public servants, public policy experts and politicians, the report explores the necessity of an impartial civil service in these uncertain times.

The following words are Institute for Government Senior Fellow and former Programme Director Jill Rutter’s contribution to this work.

If you can’t work on a policy you disagree with, don’t join the civil service! That is the founding principle of our politically impartial bureaucracy. Ministers (mostly) went to the bother to get elected and they did not. That gives them the right to choose what gets done in government – and to be held to account for that in parliament. That is not untrammelled, and accounting officers have a separate duty to ensure that public money is spent properly. But the basic message holds – if you can’t work on a policy you didn’t vote for, then lots of other careers are available.

In my early days, we all knew that the lead official on the Conservative’s privatisation programme was a committed socialist. The head of the FDA Treasury had to step down from that role when there were civil service strikes, as he was also the Assistant Secretary in charge of developing the pay policy the FDA were striking against. The Treasury made sure that any new fast streamer who joined with left-leaning credentials from their past life had an early tour of duty in “SS” – the Treasury’s social security division. When I asked my flatmate, who had joined the Treasury after a stint as a researcher to a Labour MP (and now is one herself), how she reconciled championing benefit cuts in her new job with her conscience, she said it was like football – you had to cheer for your team.

It’s no surprise that politicians who haven’t been civil servants find the ability to differentiate between your own views and the policies you are working on hard to understand.

It’s no surprise that politicians who haven’t been civil servants find the ability to differentiate between your own views and the policies you are working on hard to understand. And civil servants themselves can compound their confusion. Former Cabinet Secretary Gus O’Donnell championed his “Four Ps”, but while a civil servant could be professional, proud and pacey and stay impartial, it seemed that “passion” was a different sort of ask and one

which fitted oddly with an apolitical civil service.

Incoming government’s suspicion of civil service loyalties

Changes of government have always been difficult for the civil service. At one level, they are very exciting: the chance to work with new ministers on new policies. But they are also fraught with risk. Many civil servants have unconsciously adopted the thought processes and language of the outgoing government. Some will feel personally invested in policies they have spent time and effort developing and, in some cases, publicly defending. Some will have developed close working relationships. Ministers, especially those who have not held office before, will naturally feel more comfortable with the advisers they have come to know well in opposition than a raft of strangers who inevitably take some time to get on their wavelength. That problem has been compounded by the long gaps between government changes – 18 years of Conservative government followed by 13 years of Labour government – which meant that few incoming ministers will have prior ministerial experience.

The real danger in these transitions is that the civil service overcompensates and suspends its critical faculties in an attempt to prove that it can work with its new masters. That “candoism” means insufficient objections are raised to problematic policies like Andrew Lansley’s health reforms or the introduction of Universal Credit. But over time, the kaleidoscope settles and normal working relationships are re-established.

The principles of civil service impartiality: Thatcherism, New Labour and a Coalition government

The first two saw some real tensions emerge between ministers and civil servants. In the Treasury, Permanent Secretary Sir Douglas Wass was an early casualty of Margaret Thatcher’s premiership, with his inconvenient advice on the Chancellor’s proposed first budget leading to his side-lining. But the centre of gravity moved to a new generation of civil servants – including his two successors: Peter Middleton (who had served as Press Secretary to Denis Healey) and the externally recruited Chief Economic adviser, Terry Burns.

Terry did not long survive the advent of Gordon Brown at the Treasury – raising too many difficult questions about the fall-out of the Chancellor’s instant decision to grant independence to the Bank of England. But, again, a new generation of officials became Brown stalwarts – Gus O’Donnell, Nick Macpherson, Jon Cunliffe and Tom Scholar. Three out of four ended up as Treasury Permanent Secretaries – and the other as chief Europe

adviser to David Cameron before being poached by the Bank of England, again proving the adaptability of the top of the civil service to changed political leadership.

Referendums and the civil service

Referendums are a different sort of challenge to civil service impartiality. The Scottish independence referendum saw the UK government’s civil servants helping the government in London make the case for No. This pitted them against the Scottish civil service, which was working for the SNP government. Sir Nick Macpherson, the Treasury Permanent Secretary, gratuitously entered the debate by writing a personal minute to the Chancellor warning of the economic consequences of Scottish independence.

The EU referendum was more complicated. David Cameron relaxed collective responsibility but there were accusations that the five Cabinet Ministers who opted to support Leave were being denied access to government papers. The Leave campaign repeatedly complained that civil servants – and taxpayers’ money – were being used in the pre-official campaign period to churn out Remain propaganda. Macpherson also allowed Chancellor George Osborne to use the Treasury not just to produce a quite mainstream Treasury analysis of the long-term impacts of leaving the Single Market and Customs Union as a spuriously precise loss per household by 2030 – losing all the subtleties of the work in the process – but also publish analysis of the short-term impact of a vote to Leave, which predicted an immediate recession and which has since been dubbed Project Fear. The fact that the Treasury was not involved in the so-called “Emergency Budget” produced by the Remain campaign was not fully understood at the time and the department’s reputation has still not fully recovered, at least among some politicians.

While all these activities can be justified as “serving the government of the day”, they put the civil service onto the back foot when the government failed to secure its preferred outcome for the referendum. That was compounded by the refusal of David Cameron to allow the Cabinet Secretary to do formal contingency planning for a Leave win.

While all these activities can be justified as “serving the government of the day”, they put the civil service onto the back foot when the government failed to secure its preferred outcome for the referendum. That was compounded by the refusal of David Cameron to allow the Cabinet Secretary to do formal contingency planning for a Leave win.

“Do you believe that leaving the EU is a good thing? You personally, in your heart, are you right behind us in every single sense of that?”

Of course, Olly Robbins, the Prime Minister’s chief Brexit negotiator, batted away this question from Richard Drax MP at the Exiting the EU Committee on 5 September 2018. But it was just the apogee of the extent of distrust of the civil service by those who believe in Brexit.

That distrust has taken many forms including the accusations of obstruction by Permanent Secretaries, who former Brexit secretary David Davis MP, asserted contain no Brexit sympathisers: “If you added up all the Permanent Secretaries who voted to leave the European Union I suspect the answer would be zero”. Dominic Raab, former Brexit Secretary, also cast aspersions on government forecasts: “There is an economic credibility gap with all these Treasury-led forecasts, based on their track record of failure, the questionable assumptions they rely on, and the inherent challenge of making reliable long-term forecasts. Politically, it looks like a rehash of Project Fear.”

Suspicion of pro-EU or anti-Brexit sympathies in the civil service took concrete form in the early decision to staff the Department for Exiting the EU largely from the set of “best civil servants who have barely worked on European issues” and the speedy demise of Sir Ivan Rogers who resigned in January 2017 with an admonition to those he left behind in the UK’s permanent representation in Brussels to continue “speaking truth to power”. But they reached the apotheosis in the casting of the PM’s chief Europe adviser, Olly Robbins, as the PM’s puppet master and nemesis of Brexiteers. Hence Richard Drax’s question.

So why – almost three years after the Referendum – do ministers and parliamentarians still believe that the civil service has a hidden agenda to frustrate Brexit? At the most superficial level, former senior civil servants have very publicly and almost universally been firm advocates of the folly of Brexit and the need to reconsider. While serving civil servants do not express their views, the demographic of the policy-making class – London, graduates

(and in the case of key departments, very young) – would make it a safe bet that there is a distinct Remain majority among them.

At a second level, senior civil servants have to see through the implementation of Brexit – and that means delivering uncomfortable messages in private and public about the smoothness of preparations. The atmosphere around Brexit means raising practical objections is interpreted as hostility to the entire project.

Some Brexit supporters, such as Michael Gove, have clearly accepted their officials’ advice on the risks of a no deal Brexit; others think officials are just scaremongering. And it’s not just Brexit supporters who are critical of the civil service: former minister Lord Adonis has called out what he sees as civil service facilitation of Brexit and proposed a purge of all who worked on Brexit if he were ever returned to office.

At a third level, there is a breakdown over the way in which the UK should negotiate with the EU. Most civil servants would agree with Ivan Rogers that the UK always had a weak hand and would find it hard to get a good deal out of the EU, particularly without a clear negotiating strategy. That view ran up against the widely articulated belief from Brexit supporters that the UK “held all the cards” and that this country’s insatiable appetite for EU imports would make a good deal inevitable.

For many Brexit supporters, Brexit is an article of faith that people believe in “in their heart”. Ideas like sovereignty and autonomy are not amenable to the usual civil service approach of solving problems by looking at the costs and benefits.

But there are two final reasons why Brexit has called the impartiality of the civil service into question as never before. The first is down to the decision-making paralysis across Whitehall which has been created by the Cabinet’s chasm-like fissure over the right sort of Brexit. That fissure caused problems: with the Cabinet split down the middle, what does working for “the government of the day” really mean? And the lack of clear direction, compounded by the PM’s own secretive style, has inevitably led to speculation that the civil service has expanded to fill the vacuum.

The second reason is the nature of the debate on Brexit. While there has been much focus on a perceived clash between the will of the people and the role of parliament in a representative democracy, that is not the only schism. Brexit could be framed as a debate about values – the values of sovereignty and autonomy versus the values of collaboration – or as a debate on the cost/benefit of a trading and security alliance with the EU versus a trading and security relationship with the rest of the world. Those are very different debates, and the civil service would know to stand back on the first and to deploy its full armoury in the second.

That goes to the essence of the Drax-Robbins exchange. For many Brexit supporters, Brexit is an article of faith that people believe in “in their heart”. Ideas like sovereignty and autonomy are not amenable to the usual civil service approach of solving problems by looking at the costs and benefits. In a less contested area, it is why the civil service advised against holding the Olympics in London and left it to the politicians to say it was worth the cost and the risk. However, in the heated debate on Brexit simply asking the questions is seen as evidence that the civil service is not impartial on the project. If the reputation of the UK civil service is not to be a casualty of Brexit, those in charge need to develop a well-thought out survival strategy.

Related News

-

“Significant gaps” in current Northern Ireland standards regime, says Murtagh

FDA National Officer for Northern Ireland Robert Murtagh has called for a strengthened standards regime in Northern Ireland government.

-

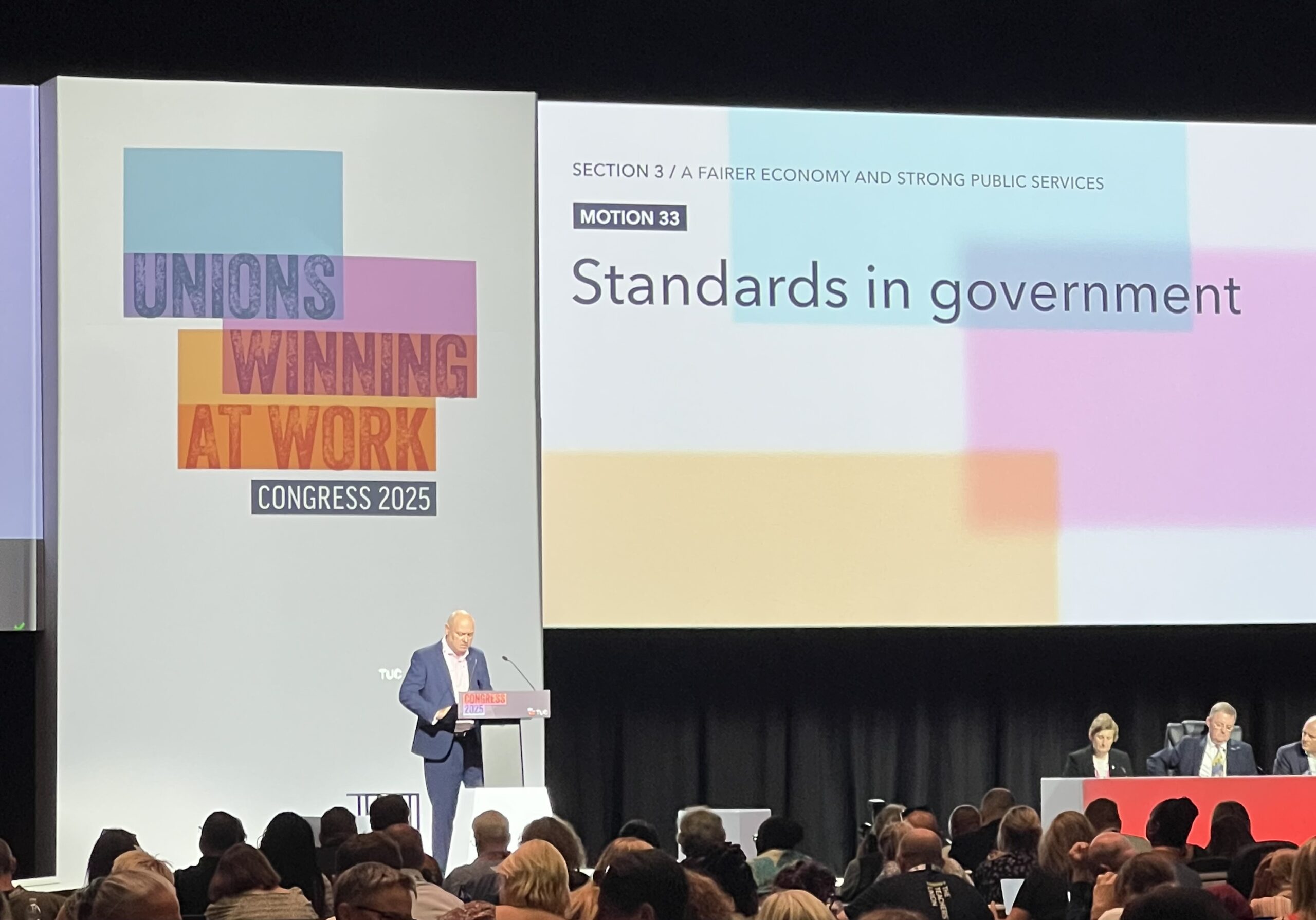

FDA delegation attends TUC Congress 2025

This week, the FDA attended the 2025 TUC Congress in Brighton. FDA delegates spoke to and moved motions on a range of topics, including standards in government, public sector productivity, resilience, neurodiversity in the workplace, and TUC reform.

-

Ministers must “step up to the plate” or risk undermining the civil service, says Penman

The FDA has defended the pay and pensions of senior civil servants and called for ministers to do more to defend the civil service.